One of the notions that is under-appreciated by urban designers and planners is that people are creatures like any other, and there are basic characteristics that we seek, or need, in our habitats.

Over thousands of years, people’s needs have been met in increasingly urban environments: as we moved out of the forests and savannahs into settlements that gradually got bigger and bigger, our species successfully adapted these towns and cities so they always met our needs – we created urban environments where we felt good and thrived.

Loss of the timeless way of building

But in the last century, many of the timeless ways of building communities have broken down, often in service of the automobile and always prioritizing speed of development over quality. Our built environments no longer reliably serve our human needs; they too seldom elevate our human condition.

To me, this is the crux of our work as peacemakers and urban designers, and I’ve become a devoted student of the art and science of restoring urban habitats that are welcoming and healthy to humans.

Placemaking and experience design

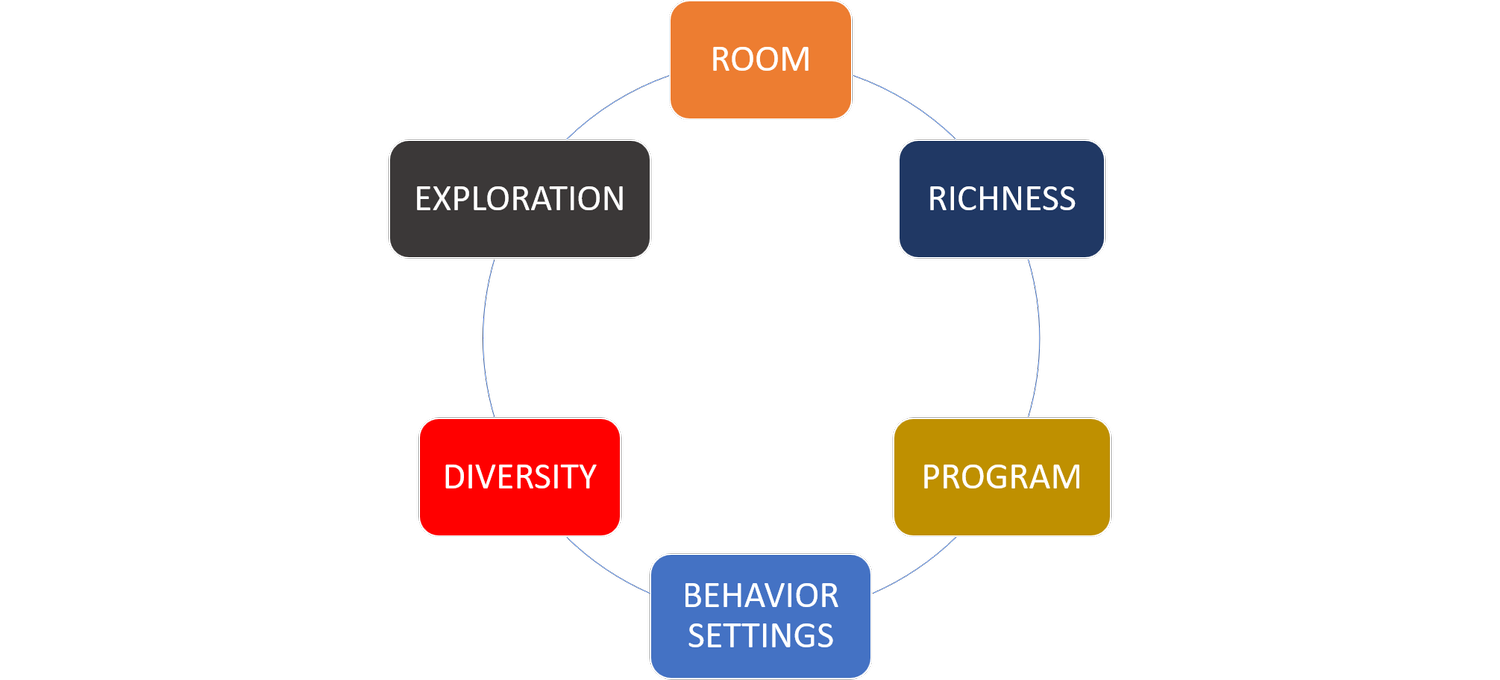

I’ve been developing a rubric (above) that I find useful as I assess or design public spaces. Some of it is adapted from what I learned at Project for Public Spaces, but much of it is what I’ve taken from methods of experience design and environmental psychology. And, of course, I learned from William H. Whyte.

I’ve always thought the work of “Holly” Whyte was related to that of Jane Goodall. As Goodall observed chimpanzees living their daily lives, equipped with a notebook, binoculars and cameras, Whyte and his acolytes (like the team at PPS) observed and documented our own species in our urban environment. Like Goodall, he opened a remarkable window on our innate behaviors, what attracts us, what drives us away, and where and how social activities take place.

Since most planning and design rarely think about their goals in terms of creating habitats, I’m putting this rubric out there in the hopes that it’s as useful to others as it has been for me. These attributes that follow are a way to evaluate the experiential qualities of any urban district or place, and by following the links you will find a deeper dive into each.

Series Conclusion

In this series, “An Ecological Approach to Placemaking,” we have examined how placemaking is not merely about constructing buildings or designing public spaces; it is an interconnected process that considers the ecological, social, economic, and psychological factors that shape our built environment. By understanding and embracing these elements, we can create places that truly resonate with the human spirit and foster a sense of belonging, well-being, and stewardship.

Throughout the series, we have emphasized the importance of a holistic approach to placemaking, one that recognizes and prioritizes the diverse needs of both people and the natural environment. We have delved into the significance of incorporating natural elements into our urban landscapes, the value of engaging our senses and innate need for exploration, and the crucial role of community engagement and social interaction in creating places that are truly alive and thriving.

As we move forward in our collective efforts to create sustainable, resilient, and livable communities, it is essential that we continue to learn from and be inspired by the wisdom of nature. An ecological approach to placemaking offers us a valuable framework for understanding the complex relationships between humans and their environment, and for designing spaces that are responsive to these relationships.